The trillion-dollar remittance pipeline draining U.S. wealth

![]()

A recently proposed U.S. tax on remittances sent abroad by non-citizens has exposed a truth few Americans have been told – that the United States has become a primary financial engine of the Indian economy.

The provision, quietly included by the House Ways and Means Committee in a broader legislative package introduced on May 12, commonly referred to as the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill,” initially proposed a 5% tax on international money transfers by non-citizen visa holders and green card recipients. The goal was straightforward: to recoup a small portion of the vast sums of untaxed income being sent out of America every year.

But the backlash from Indian government officials, media outlets, lobbying groups and diaspora advocates was swift and intense. Within weeks, the rate was reduced to 3.5%.

What triggered such fervent opposition? The answer lies in the numbers.

$1 trillion and counting: What Americans haven’t been told

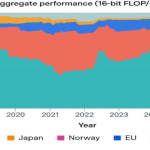

According to India’s own financial disclosures and public-facing documents, over the past decade the country has received nearly $1 trillion in foreign remittances – that is, transfers of money from a migrant worker back to their home country. A disproportionate share of those remittances originate from Indian workers within the United States. In fiscal year 2023-24, India banked $125 billion in remittances, the U.S. contributing 27.7% or approximately $34.6 billion, making the U.S. India’s single largest source of foreign income.

By comparison, India’s Foreign Direct Investment inflows during the same period stood at just $62 billion and its entire national defense budget in 2024 was nearly $55 billion less than the remittances it received.

In short, Indian nationals working in the U.S. are sending home more money than India attracts in global investment and more than it spends defending itself.

Financial dependency with strategic implications

\Indian officials have acknowledged what few in the U.S. government seem willing to: These remittances serve as a vital “cushion” to cover current account deficits and stabilize the value of the rupee against the dollar. In economic terms, this means India relies heavily on money earned by Indian nationals abroad – particularly in the U.S. – to maintain internal stability.

But this dependency is not passive. It is the product of deliberate policy. The GATI Foundation is one key initiative, which, is a state-orchestrated program designed to export millions of Indian workers, skilled and semi-skilled, into high-income economies like America’s, with the explicit objective of capturing jobs in the host country. A key purpose of this program is maximizing inward remittance flows to boost the remittance share of India’s GDP from 2.5% to 4-5%, resulting in an increase of $300 billion annually.

Marketed as a solution to a projected “global labor gap,” GATI seeks to institutionalize India’s dominance over international labor markets, reshape global migration policy and position India as the world’s “trusted migration partner.”

The GATI Foundation and the government of India see this as an opportunity to offload India’s mounting youth unemployment and domestic jobs crisis onto the labor markets of the U.S., U.K., Germany, Japan and others, directly undermining native workers while driving huge remittance flows to fuel India’s own growth.

A modest U.S. tax is met with international uproar

The legislative proposal in Washington was modest by any global standard. The reduced 3.5% remittance tax would apply only to non-citizens on temporary work visas or with lawful permanent residency sending money out of the U.S. Yet Indian media outlets, think tanks and government-linked analysts labeled it a “discriminatory measure targeting non-U.S. citizens,” “politically motivated” and even an effort to force “self-deportation” among Indian professionals.

This dire narrative, amplified by both foreign and domestic lobbying efforts, suggests the very limited measure is xenophobic and unfairly targeting Indians. India’s media outrage reveals the sense of entitlement of that nation and its elites, who believe they are owed unfettered access to U.S. wages, and that any attempt to recoup even a small portion of that wealth is a sure sign of their victimhood. Indian trade groups warned the tax would deter “global talent” and threaten bilateral relations between India and the U.S.

According to economic think tank Global Trade Research Initiative, the Republican-backed proposal to tax remittances would have severe economic impact to key allies to the U.S., like India, who has been the top recipient of U.S. remittances. GTRI further stated, “The proposed U.S. tax on remittances sent abroad by non-citizens is raising alarm in India, which stands to lose billions in annual foreign currency inflows if the plan becomes law.”

In other words, the tax threatens a revenue stream that India has quietly come to depend on without compensation to the country that enables it.

An uncomfortable question: Who pays for India’s gains?

While Indian nationals abroad are encouraged to remit money back to their homeland and often celebrated for doing so, the economic impact on the host nation remains largely unexamined.

Each dollar sent abroad is one not spent in the U.S. economy, not invested in American infrastructure and not taxed at the federal or state level once it leaves the U.S.

U.S. employers, many of whom sponsor temporary work visas, benefit from lower labor costs. But American workers bear the brunt of wage competition, job displacement and the broader economic hollowing that comes from capital flight through massive numbers of foreign workers in the U.S.

There is also the civic imbalance, with many of the individuals sending billions abroad being protected by American laws, benefitting from American services and living in American communities while directing their earnings to a foreign government’s macroeconomic agenda.

Beyond economics: The geopolitical dimension

India’s policy toward its diaspora is not merely economic; it is political. As outlined in official documents from its Ministry of External Affairs, India encourages its overseas nationals to invest in Indian assets, vote in Indian elections and lobby foreign governments including the U.S. to advance India’s interests.

This creates a troubling duality where foreign nationals living and working in the U.S. are expected to function as de facto agents of India’s domestic and foreign policy, while remaining outside the full obligations of American citizenship.

The remittance tax, then, is more than a financial issue; it is a test of sovereignty, accountability and national interest.

What comes next? A national conversation long overdue

The remittance debate has revealed a broader and more urgent question: How should the United States manage the intersection of immigration, labor and outbound capital? India’s response to the proposed tax has shown just how entrenched the expectation of American subsidization has become. But the larger issue is not India’s behavior, it is America’s inaction.

A trillion dollars in foreign transfers should not go unnoticed. Nor should the policy frameworks that enabled it.

It is time for U.S. lawmakers, economists and voters to confront the reality that remittances are not neutral. They are not charities. And they are not free. They are a transfer of wealth – often untaxed, frequently unexamined and increasingly misaligned with the long-term interests of the American people. If America is serious about protecting its economy, labor force and global position, it must begin by asking a simple question:

How much more can America afford to give away before there’s nothing left to protect?