While the government’s ownership is passive, or nonvoting, it will still have some influence over the company.

Some have suggested that the deal amounts to government meddling in the private sector or even signals that the nation is moving away from a free market to state capitalism.

Trump administration officials have pushed back on characterizations likening the move to socialism, saying the agreement will boost U.S. leadership in semiconductors.

The deal forms part of a broader trend as Washington steps up its efforts to win the U.S.–China tech race, experts told The Epoch Times.

While they were split on how to identify the trend—state capitalism or something else—the experts agreed it was a necessary move to compete against an economy directed by a regime that doesn’t play by established trade rules.

Washington cannot win the tech race by just controlling Beijing’s access to advanced U.S. technology, the experts said. It also needs to exert pressure on China’s economic model.

For years, the Chinese regime has been flooding the global market with inexpensive products made possible by its excessive manufacturing capacity. That, in turn, makes money for tech development.

Intel’s Strategic Value

Under the deal, the Department of Commerce converts its $11.1 billion grant provided to Intel under the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act into nonvoting shares. Additionally, within five years, the U.S. government has the right to acquire another 5 percent share if the company decides to reduce its ownership stake in its chip manufacturing, or foundry, business to below 51 percent. That’s the “foundry clause.”

The federal government has taken ownership of private companies before. However, that was typically done during an emergency, such as the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic.

Intel’s current woes are not due to broader market conditions but poor management decisions.

James Lewis, a former diplomat specializing in technology and a distinguished fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, calls Washington’s new approach “state capitalism.”

Intel doesn’t get new money, he told The Epoch Times, and taking a stake in Intel without a board seat doesn’t really help solve the company’s problems.

William Lee, chief economist at the Milken Institute, however, thinks it’s too early to conclude it’s state capitalism because Intel is a unique case, and the government’s ownership is passive.

Lee describes the approach as a “national defense strategy that includes economic assets.”

“China’s attack on the U.S. is most likely going to be cyber, software-related, and tech-related,” Lee, who also leads the consultancy Global Economic Advisors, told The Epoch Times. “That’s why we want to have our own tech industry. Because that’s where the battleground is going to be.”

From a national security perspective, Intel has unique value because it’s the only American shop with advanced chip design and manufacturing under one roof.

Washington’s move is “preemptive” in using state capital to prevent the talent and technology of a high-tech company from being transferred to other countries, Ethan Tu, founder of Taipei-based Taiwan AI Labs and a veteran practitioner in the AI field, told The Epoch Times.

Tu said the company still hosts key technologies powering central processing units, or the brains, of electronic systems.

A Unique Deal

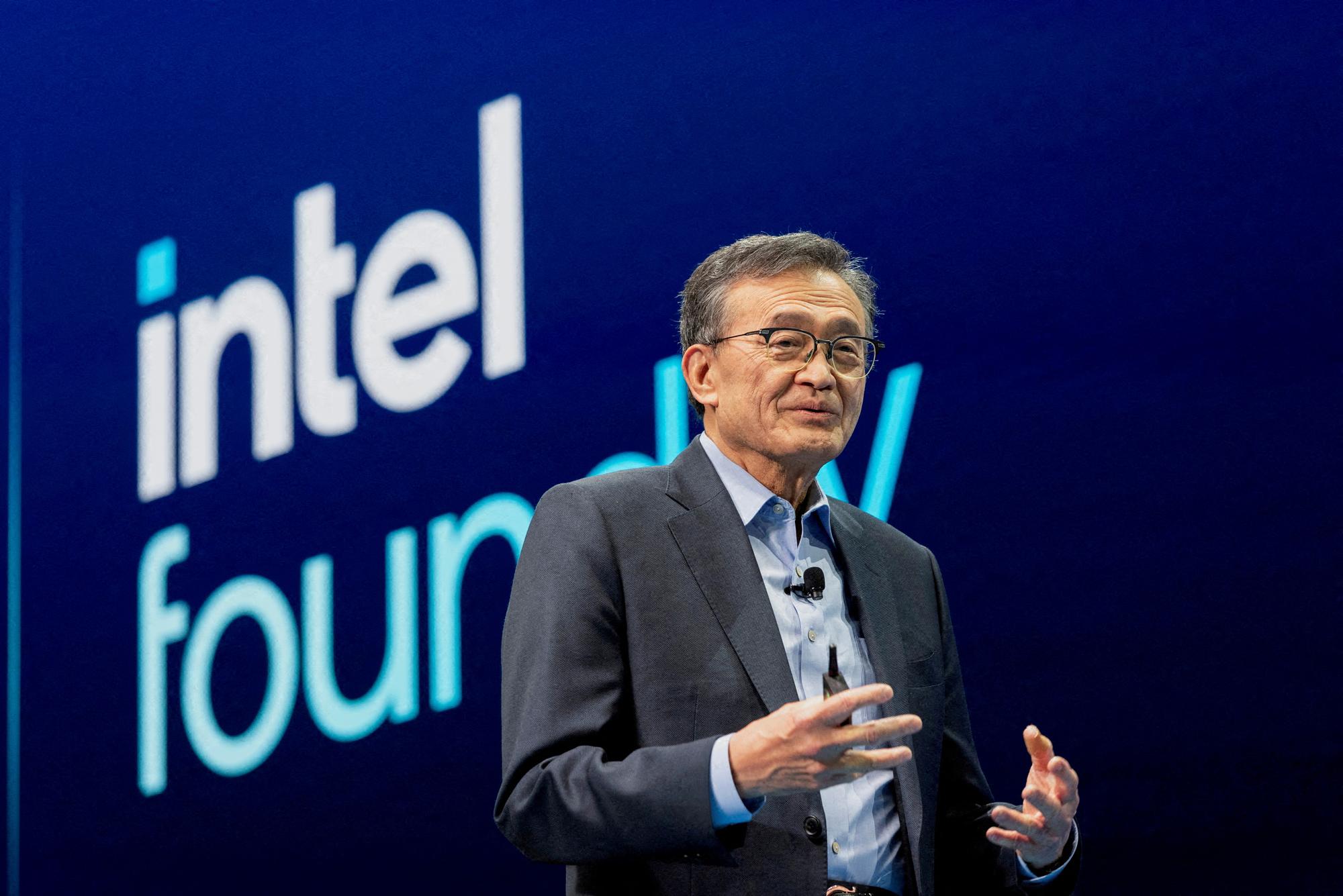

On Aug. 11, days after President Donald Trump called for Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan to resign over alleged ties to China, the two met at the White House. Reports began to emerge about the U.S. government taking an equity stake in the company. The deal was officially announced on Aug. 22.

On the same day, Trump said he discussed the idea of a 10 percent stake with Tan during their meeting.

Investors reacted to the Intel deal with both cautious optimism and unease.

Intel seems to be a specific case, but the deal is still “scaring the [expletive] out of everybody,” according to Andrew King, a general partner at Bastille Ventures. He is also the president of Future Union, an advocacy group that encourages the private sector to disengage from adversarial countries, such as China and Russia.

Intel needed the money, and the government provided a capital injection that might be otherwise unavailable to the company, King said.

However, he said that it’s still “unnerving” to Wall Street because if the government wants to take a stake in another company that doesn’t need the money, can a company say “no?”

Officials at the administration have defended the Intel deal.

White House spokesperson Kush Desai told The Epoch Times that by converting federal grants into an equity stake, the administration was “ensuring that taxpayers are able to reap the upside of the federal government’s investments into safeguarding our national and economic security.”

Fighting China’s Unfair Practices

The Intel deal is not the first case of a government taking a stake in the U.S. private sector.

During the ongoing trade negotiations, rare earth magnets have emerged as a key vulnerability for the United States and other Western countries. Their strong magnetic fields, independent of power sources, are a crucial element in modern manufacturing and advanced weaponry.

Both advanced chips and rare earth magnets are essential components in determining technical leadership.

Because the tech race will be a defining aspect of the U.S.–China power competition, this new approach—involving the U.S. government taking ownership in private businesses in strategic industries—is likely to expand to more companies and sectors, according to China expert Alexander Liao.

The U.S.–China race is currently at a critical juncture, he said. In his view, China has sustained its technical development primarily by acquiring technology through theft and by dumping products from its overcapacity to generate revenue, thereby supporting its industrial policies.

Tariffs on Chinese exports have exerted significant pressure on China’s economy, shrinking its access to the overseas market. Along with export controls, this has also brought challenges to its technical sector.

Liao said that if China’s tech sector can maintain its pace of development for another five to 10 years, then the U.S. private sector might not be able to compete, even with Uncle Sam’s support.

Lewis concurs that China is “dependent on stealing technology as much as they once were.”

China is already a peer in many tech areas, he said, despite problems with “bad investment decisions” and the “ability to create the political space for innovation.”

Lewis believes Trump correctly identified the problems stemming from Beijing but did not respond with the right fixes.

King agrees that the government owning private businesses is not an optimal solution. “You’re going in at a disadvantage with companies that are not leading,” he said.

However, King also views it as the best option available.

“My simple point of view is when your competitors and competitive geopolitical nation-states are playing dirty, then you find whatever tools you have in the toolbox to compete and win,“ he said, ”and that’s what we’re doing right now.”