The long-awaited U.S.–China meeting in South Korea last week ended with a truce that lowered tariffs and halted a spiraling trade war between the world’s two biggest economies.

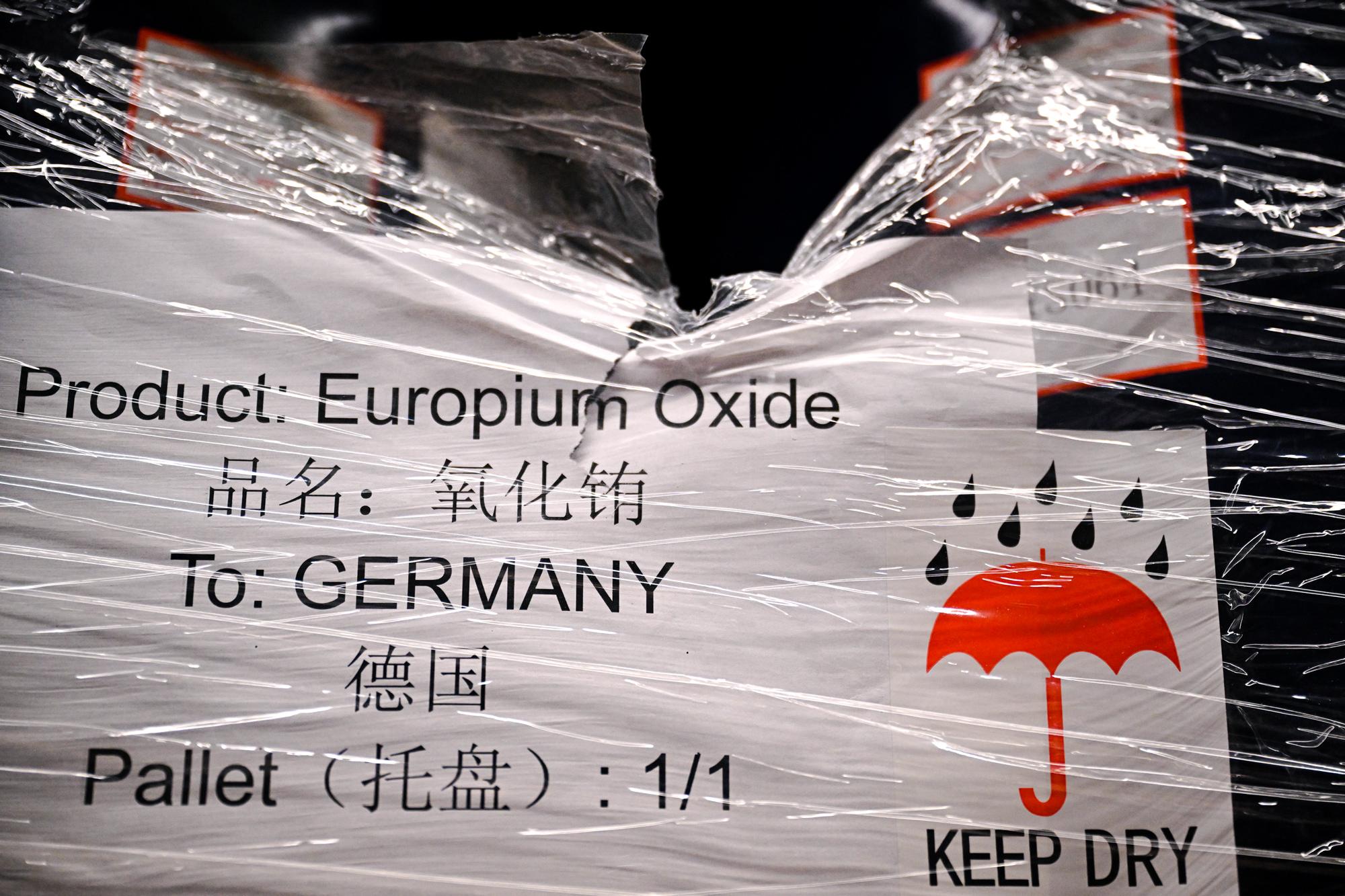

China is now buying soybeans again after a months-long hiatus. The rare earth minerals will flow out again. And the tit-for-tat port fees are on pause.

The two national leaders both hailed the meeting as highly positive. President Donald Trump rated it a 12 out of 10. Xi Jinping called it “a new start.”

But behind the friendly banter, the question of how long the detente lasts—and whether the regime will renege on its promises—is another matter.

“It’s a diplomatic painkiller,” Sun Kuo-hsiang, an international affairs professor at Taiwan’s Nanhua University, told The Epoch Times. “It alleviates the symptoms for the moment but leaves the root cause untouched.”

“Most cease-fires are very fragile. They don’t last a long time,” Balding, founder of New Kite Data Labs, an open source intelligence entity that researches the Chinese economy, told The Epoch Times.

A Delay Game?

The landmark meeting on Oct. 30 was the first face-to-face encounter between Trump and Xi in more than six years.

After their 100-minute talk, Trump said the two “agreed on many things, with others, even of high importance, being very close to resolved.”

With the agreement came a rollback of threats and retaliatory measures from the preceding months. China’s reciprocal tariffs, imposed since March, will pause and American soybeans purchases will resume. The sweeping rare-earth export controls from October will stop for a year. Beijing also promised to cut down smuggling of fentanyl precursors in return for a 10 percent China tariff cut.

But absent from the deal are glaring issues that overshadow the bilateral relationship. Among them are the fate of Taiwan, human rights, China’s military aggression in the Indo-Pacific region, structural issues with China’s industrial policy, TikTok, and semiconductors.

“There’s a lot of issues that they just didn’t deal with,” said Balding. Sooner or later, he said, these issues will come back and break the temporary calm.

Beijing has indicated it will fight for core interests. Several days after coming to the deal, Chinese Ambassador Xie Feng brought up Taiwan and human rights as among Beijing’s “red lines” in a video address. The U.S. side, he said, should “avoid crossing them and causing trouble.”

Even the existing pledges remain abstract and tentative, Sun noted. The trade deal is up for review yearly. So are the loosening of Chinese rare earth restriction and Washington’s suspension of duties on China-linked vessels. During that time, any geopolitical headwinds, from Russia-China relationship to Taiwan Strait tensions, could cause priorities to shift, Sun said.

The lack of details in the agreement gives Beijing a loophole to exploit, according to Yeh Yao-yuan, department chair of international studies at the University of St. Thomas.

“Talking one way and acting in another—this is typical of the Chinese Communist Party,” Yeh told The Epoch Times.

With the U.S.–China pact short on specific targets, if China fails to hit them, he said, the regime can play the delay game and not deliver anything tangible.

False Hopes

The gap between promises and reality is a constant concern in Washington’s dealing with China.

In his first term, Trump sought to address Beijing’s unfair trade practices and the massive U.S.–China trade deficit by launching a trade war.

“The Chinese Communist Party doesn’t have a very good history on keeping promises,” Lucia Dunn, professor emeritus of economics at Ohio State University, told The Epoch Times.

Yeh called it doublespeak.

“Anything that doesn’t go in its favor, the communist party just won’t do it,” he said. “It will keep pushing them off.”

Decades of market manipulation, strategic state support, and aggressive investment allowed China to capture rare earths and effectively hold the world to ransom. The recent export curbs are now spurring a reckoning.

Forced Concessions

China has come to the negotiating table with a crisis brewing on the homefront.

In Kangle Village, a once thriving garment hub in southeastern China, people crowd around hunting for odd work. With jobs drying up, migrant workers in several cities have packed up early for home; one major textile factory sent their entire workforce for a four-month vacation, citing dwindling orders.

Weighed down by such economic pressure, China is seeking breathing room, analysts say.

“Xi has to make concessions—only that they are half-hearted concessions,” said Yeh.

Still, both sides appear eager to disentangle from each other.

“We’re going to go at warp speed over the next one, two years, and we’re going to get out from under the sword that the Chinese have over us—and they have it over the whole world,” said Bessent.

The ‘New Norm’

Bessent says the United States is looking to “de-risk” rather than decouple. But Balding said those are just buzzwords.

“I think you’d be hard pressed to find clear definitions of those,” he said. “I’m not stuck on a word.”

In the long term, decoupling seems to be the inevitable trend, says Wang Guo-chen, a research fellow at the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research.

“Both are preparing to decouple, it’s just that for now, neither is ready for the costs,” Wang told The Epoch Times.

The new dynamic marks a shift from the “mutual dependence and mutual benefit” that China has long promoted, according to political economist Davy J. Wong.

“Security and autonomy is the new norm,” he told The Epoch Times.

This makes any cooperation fleeting by nature, said Yeh.

“When you are partners, everything is easy, but now the relationship has changed from partnership to competition, and not just any type of competition—it’s a life and death battle,” he told The Epoch Times.

On a deeper level, the split between Washington and Beijing is ideological, analysts say.

The Chinese word for China translates into “the Middle Kingdom” in English. While people in the West often understand the word “middle” to mean “between,” the actual idea is closer to the center, like “the planets revolve around the sun in the middle,” said Balding.

“That’s how China thinks of itself,” he said. “It thinks it’s returning to the place it belongs, as the center of the world, as the center of the universe around which all other states and issues revolve.”

“That puts it in very much fundamental disagreement with the United States to start off with, but a lot of other countries from there as well.”