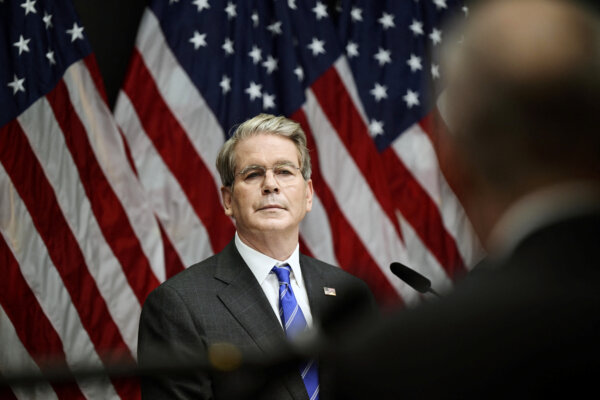

![]() Remarking on the ongoing U.S.–China dispute over rare earth exports, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said during an Oct. 15 press conference that if Beijing refuses to act as a reliable trading partner, the United States and its allies may have no choice but to decouple.

Remarking on the ongoing U.S.–China dispute over rare earth exports, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said during an Oct. 15 press conference that if Beijing refuses to act as a reliable trading partner, the United States and its allies may have no choice but to decouple.

While emphasizing that decoupling—severing trade ties entirely or nearly so—is not Washington’s desired outcome, Bessent said it could become unavoidable given China’s posture in the current standoff over rare earths supplies.

He noted that U.S. auto manufacturers have recently reported slowed shipments of China-made magnets containing rare earth elements, with Chinese officials offering non-credible explanations for the delays.

“If China wants to be an unreliable partner to the world, then the world will have to decouple,” Bessent said. “The world does not want to decouple; we want to de-risk. But signals like this are signs of decoupling, which we don’t believe China wants. And again, we do not want to decouple. We should work together to de-risk and diversify supply chains away from China as quickly as possible.”

On Oct. 15, Bessent said that talks with Chinese counterparts are ongoing and reiterated the administration’s stated intent to avoid escalation.

“As the president said, we want to help China, not hurt it. If some in the Chinese government want to slow down the global economy through disappointing actions and economic coercion, the Chinese economy will be hurt the most,” he said.

“And make no mistake, this is China versus the world. They have put these unacceptable export controls on the entire world.”

“When we get an announcement like this week with China on rare earths, you realize we have to be self-sufficient, or we have to be sufficient with our allies. So when you are facing a non-market economy like China, then you have to exercise industrial policy,” Bessent said.

He said that for 20 years, anytime that a business in a market-based economy launched or refined a process, China would come in and undercut the pricing in order to put the company out of business.

“So we’re going to set price floors and have forward buying to make sure that this doesn’t happen again. And we’re going to do it across a range of industries,” Bessent said.

When asked about the scope of such industrial policy—specifically whether the administration might take stakes in pharmaceutical or defense firms—Bessent said it wouldn’t need to go that far.

“We may have to, as their biggest customer, prod them to do a little more research and … do a little few stock buybacks,” he said.

Responding to a question about critics calling such measures “socialist” or accusing the government of picking winners and losers, Bessent stressed a need for restraint.

“We do have to be very careful not to overreach,” he said. “We need to go back and examine, ‘Okay, have we accomplished our goal?’ and then move on.”

He noted that years of lax industrial policy enabled China’s rare earth dominance and left the United States vulnerable.

“We have to be vigilant. For 20 to 25 years, we haven’t been vigilant,” he said. “The leading Chinese rare earth company used to be owned by General Motors. The Chinese bought it in 1995. CFIUS, which I chair, the Committee for Foreign Investment in the United States, mandated that it stayed in the U.S. for five years. Guess what happened? Five years and one day, it went back to China.”

Bessent said this happened because “nobody was watching.”

“Everyone was asleep at the switch. So, we’re just not going to be asleep at the switch,” he said.