Randy Wang, a 28-year-old factory supervisor living in a coastal city in China, is seriously considering giving up on hard work, or what’s now known in China as “lying flat.”

Until recently, doing just enough to get by wasn’t an option for him. Although many young Chinese have joined the “lying flat” movement because they can’t see how hard work would make a difference in their lives, he hasn’t been one of them.

Mr. Wang chose to use a pseudonym because of a fear of reprisal from the Chinese regime.

A son of a rural Chinese family, he bought an apartment in late 2020, just three years after graduating from college. At that time, he was optimistic about the future.

Mr. Wang’s 1,100-square-foot apartment has since lost one-fifth of its original value of 1.2 million yuan (about $176,000). Even if he wanted to sell it, few are buying. He still owes the bank 880,000 yuan (about $124,000), or more than 90 percent of the current property value.

To find a way out, he used a credit card to invest 100,000 yuan (about $14,000) in the stock market in February 2023, holding a mix of state-owned enterprises and private companies. Since then, China’s stock market has been

falling. By November 2023, he had less than 40 percent of his initial investment left. To stanch further loss, he cut his losses and sold his stock, describing it as a “very painful” decision.

China’s stock rout “added insult to injury,” Mr. Wang told The Epoch Times.

Even though last year was difficult, he said, “I think 2023 was the best year in quite a few to come.”

Mr. Wang hasn’t seen any signs that indicated otherwise.

As it stands now, his net worth is negative. Mr. Wang’s total housing and credit card debt is about 1.5 million yuan; he owns an apartment that he may be able to sell at 950,000 yuan, and he doesn’t have any savings. An additional credit card debt of 600,000 yuan was incurred for the apartment’s renovation, his father’s medical expenses, and previous losses in the stock market.

He has been robbing Peter to pay Paul to manage different credit cards and payment deadlines each month. Orders at his factory don’t show any signs of increasing, alluding to a gloomy picture.

“At some point, I will have to declare bankruptcy,” Mr. Wang said.

First, he said, he would sell his apartment so the credit card company couldn’t take it. Then he would stop paying off credit card debt and start living on cash.

“I don’t know if I have any other options,” Mr. Wang said.

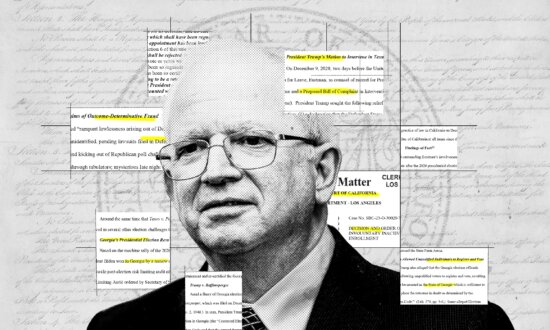

Stock activity is displayed above a security guard as he stands outside the Exchange Square towers in Hong Kong on Nov. 4, 2020. (Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images)

He has noticed small businesses struggling in his neighborhood. The noodle place that he frequents has changed ownership six times in the past 12 months. Traffic flows in shopping malls have also shrunk; famous food court delis that used to have long lines and average wait times of 30 minutes or longer before the COVID-19 pandemic are now half-empty.

“I couldn’t even afford one round of trial and error if I were to open a small business,” Mr. Wang said, indicating that he has exhausted all options for a financial breakthrough.

He considers his case emblematic of a large group of people in China as he isn’t one of the urban youth whose family can provide substantial support in times of financial difficulties.

“I’m from a rural area. My family isn’t that well-off. A lot of people are in similar situations,” Mr. Wang said. “I think I’m more hardworking than many others. If even I am in such a bad situation, you can imagine how many others are struggling.”

He believes that China’s economy is in recession.

“As long as you live in this country and observe what’s going on around you, you see the signs for sure,” Mr. Wang said.

The Recession

“China’s recession is hiding in plain sight,” Yardeni Research, a New York-based global investment consultancy firm, wrote in a client note in late January. “It is the result of a major negative wealth effect caused by plunging real estate and stock prices.”

The Chinese stock market has

lost more than $6 trillion since its peak in early 2021. The MSCI China Index is

down by about 60 percent during the same time period, according to Bloomberg data.

China’s recession began in about November 2022, when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) initiated the three-batch liquidity package—known as the “three arrows” policy—to help real estate developers gain access to bank loans, bonds, and equity markets for more money, according to Edward Yardeni, president of Yardeni Research.

The Evergrande logo is displayed on residential buildings in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China, on Oct. 25, 2023. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

He thinks that the recession will last one or two more years before China enters into economic stagnation at a zero to 2 percent growth rate for 10 to 20 years.

To him, China’s 5.2 percent official gross domestic product

(GDP) growth rate—slightly higher than the 5 percent official forecast—isn’t consistent with other indicators in the market, such as low copper and oil prices driven by weak demand from China and the mass value loss in the stock market.

“In our opinion, we are seeing the beginning of a major debt crisis in China,” Yardeni Research’s note reads.

According to the firm, Chinese bank loans increased almost eightfold between December 2008 and December 2023, or to $33 trillion from $5 trillion, compared to U.S. bank loans doubling to $12 trillion over the same period.

Even though the world may not ever see a recession per its official definition—negative economic growth in two consecutive quarters—reflected in China’s data, all indicators suggest a recession, Mr. Yardeni told The Epoch Times.

He’s not the only one questioning China’s statistics.

The Rhodium Group, a leading research firm on the Chinese economy,

estimated China’s GDP growth last year to be about 1.5 percent.

Cai Shenkun, an independent Chinese writer and commentator, said the CCP cooked the 5.2 percent growth rate by lowering the previous year’s base.

On Dec. 29, 2023, China’s National Bureau of Statistics

announced that it was retroactively decreasing the 2022 GDP by 500 billion yuan (about $70 billion) because of “final data verification.” The impact of the adjustment is about 0.5 percent of growth.

In late January, Mr. Cai

pointed out that the provincial-level 2022 GDP decreases didn’t match the national total. A few days later, the BBC

reported similar data issues.

“The central CCP set the tone of 5.2 percent; they then released 5.2 percent. They tried to fake numbers, but it’s impossible to make the lies consistent at all levels,” he told The Epoch Times.

“It’s a completely shameless approach. They don’t care if the numbers are real or fake.”

Belt-Tightening

Amelia Li, a 27-year-old freelance reporter covering the economy in Beijing, told The Epoch Times, “Everything around me is comprehensively downgrading.”

By that she means that consumers, including herself, are looking for cheaper substitutes, ranging from food and beverages to travel. Ms. Li also uses an alias to protect her job.

She said Chinese domestic coffee and milk tea chain stores are expanding into lower-tier cities because the consumption in urban markets is too low to support their costs. However, the article that Ms. Li wrote about this trend had to pass censorship controls, so she had to tell the story as if consumption levels had grown in small cities.

People walk in a shopping mall in Beijing on Jan. 16, 2024. (Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images)

She said it’s a “strange feeling” to visit shopping malls in Beijing—the eateries in the food courts are crowded, but not many people shop in the stores.

The most popular eatery is a place that Ms. Li said sells “10-yuan [about $1.40] low-quality carbohydrates” and “a bowl that will keep you full but, without doubt, will raise your sugar level and make you fat.”

Beyond cheap meal sources, she has noticed that businesses offering more affordable alternatives are selling well. But profit is another story.

Instead of buying a new down jacket for the winter as in past years, young Chinese are

getting the military coat of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) this winter. A military coat may be bought for slightly more than 30 yuan (about $4), while a down jacket costs at least nine times more.

Yet the military coat’s dark green color and style aren’t very favorable to young people, so vendors with improved styles are seeing higher demand.

Unlike Mr. Wang, Ms. Li said she has already “lain flat.”

Originally from the capital of a northeastern province, she lives outside the Fifth Ring Road in Beijing—on the poorer side of the demarcation line for socioeconomic status—near a big logistics center in Beijing’s Shunyi District, northeast of the city’s urban core.

Unlike in the United States, wealthier Chinese live closer to the city center. Ms. Li’s neighbors are either restaurant owners who want to save up to send money to their hometown or laborers relying on daily work.

“I feel that I’m no different than those who get paid daily,” the freelance writer said. “My living condition is not much different. I’m living one day at a time.”

Ms. Li doesn’t have health insurance. With an average monthly income of 5,000 yuan (about $700), she relies on cheap meals from local eateries. When she traveled to multiple provinces late last year, she took slow local trains all the way through, avoiding the more expensive high-speed ones.

Folks around her have skipped the typical overseas travel to Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand and focused on visiting domestic places.

A customer shops for fruit and vegetables at a supermarket in Fuyang, in eastern China’s Anhui Province, on Feb. 8, 2024. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

A law professor in southern China’s Guangdong Province—a coastal area instrumental in the country’s achievement of becoming the “world’s factory”—said the youth and people working in the private sector in her province were the first groups hit by fallen exports.

The 42 million migrant workers make up about one-third of the province’s population. The decrease in their income, which is sensitive to exports, has driven down the overall consumption in Guangdong.

The professor spoke to The Epoch Times on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals.

China exported $3.38 trillion worth of goods in 2023, down by 4.6 percent from 2022 and a first-time drop since 2016.

People employed in state-owned enterprises and government-owned entities, including public universities, are currently less affected because they commonly claim reimbursements for food, medical expenses, and travel.

However, the professor said, like her, many public-sector employees haven’t received a bonus for three years and that their employers sometimes take back a few thousand U.S. dollars per year, claiming that employees still owe taxes, dubbed a “tax true-up.”

According to her, government officials don’t dare to discuss decreased compensation for fear of losing their jobs. But she knows that the decrease is happening because government officials and others in the public sector use the same compensation system that she does.

As the government’s tax revenues keep shrinking, the professor expects the worsening economy to hit public-sector employees by the end of this year, affecting their salaries next year.

“The local governments have no money; their finance departments are saying that,” she told The Epoch Times. “They are trying to get more money through ‘tax true-ups’ and new fines, channels that will dry up someday. With less tax revenues because of the bankruptcy of private companies over fallen exports, we will feel the pain soon.”

A worker polishes steel rims at a factory producing bicycle parts for export in Hangzhou, in eastern China’s Zhejiang Province, on Feb. 18, 2024. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Damage Control

Bloomberg reported on Jan. 22 that China has weighed injecting 2 trillion yuan (about $278 billion) into the stock market to prevent further decline.

Two days later, China’s central bank

cut the banks’ reserve requirement ratio by 0.5 percent, effective on Feb. 5. The cut—the

deepest since December 2021—would release about 1 trillion yuan in the form of new loans.

On Feb. 6, Central Huijin Investment, the equity arm of state-owned China Investment Corp,

announced increasing holdings of mainland stocks. As a result of the series of measures, China’s stock indexes jumped by a few percentage points, ranging from 3 percent in Shanghai and Hong Kong to 7 percent in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange Index.

“The CCP wants to create an impression that there’s still money to make in China’s stock market,” Mike Sun, a U.S.-based businessman with decades of experience advising foreign investors and traders doing business in China, told The Epoch Times.

He said, therefore, that when the U.S. Federal Reserve cuts interest rates later this year—a current Wall Street consensus—some investors looking for a higher rate of return may move their capital to China. At the same time, a moderate stock rebound wouldn’t give many investors whose portfolios are down by 60 percent or 50 percent enough incentive to pull out of the equity market.

But Mr. Yardeni doesn’t believe that U.S. investors will put more money in China’s stock market after the Fed cuts rates because “they had been turned off to investing in China.”

“The stock market has been sending a negative message, maybe telling the truth, about what’s going on there—that their economy really is in trouble,” he said.

“And they like to keep the image of the Chinese economy doing well under their leadership. It’s for damage control.”

Traders work on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange during afternoon trading in New York on Feb. 5, 2024. (Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)

According to Henry Jia-Long Wu, a senior political economy commentator based in Taiwan, the cause of the crisis lies squarely at the feet of the ruling regime.

“The root of the present crisis is in Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s policy and the CCP,” he told The Epoch Times.

“The market economy is characterized by competition through innovation, while socialism pursues control through power.

“Therefore, the Xi government is not friendly to private businesses and the Chinese economy will see the private sector lose energy in the future. That will be a big problem for the Chinese economy.”

Mr. Wu said the export-driven Chinese economy has been suffering from U.S. tariffs and technology controls.

“Moreover, the uncertainty due to the absence of reliable macroeconomic data leads to foreign capital flight and the loss of confidence in the economic outlook,” he said.

“Eventually, there will be more downturn pressures to prolong the ongoing recession.”

For the past three decades, consumption, exports, and investment have been widely recognized as the Chinese economy’s “troika,” or the three leading drivers.

Last summer, Chinese political commentator Qin Peng proposed a new troika—the National Bureau of Statistics, the CCP’s Propaganda Department, and the Cyberspace Administration of China—for faking economic data, promoting a picture of economic recovery and growth, and eliminating conflicting messages to the official story.